The STUDS/Group 1: FIRST AND LAST

Many things happen in the span of twenty-five years. It is hard to find an object that will last that long, much less an activity. When I began to carve cars in January of 1984, I was a busy man trying to be the sole provider for a wife and two-year old child while working as a lab technician at the Florida Department of Transportation’s Bureau of Materials and Research in the asphalt testing lab. I was living in an old wooden house with no heat and depending on a 12 year old Datsun 510 with over a hundred thousand miles on it to take me the twenty-five miles to work each day. Volunteering to help someone in the community took precious time from the other duties in my life and brought scorn from an overbearing wife. When I received that first Pinewood Derby car as a gift from a man at church, I did not realize that the gift I was given turned out to be a passion that has continued to burn in my soul after twenty-five years instead of a box with a block of wood, plastic wheels and nails in it. Armed with the determination and the dreams of youth but lacking the skills and resources, I began a quest that year to build the fastest and most unique Pinewood Derby car the town had ever seen.

The cycle of life presents opportunities for both pain and pleasure with knowledge as the by-product of the endeavor. After carving that first car I realized the activity satisfied the creative drive that is ingrained in my being. I looked forward to the times where I could spend time with a block of wood. The process allowed me the time to relax and escape the drudgery of my crazy life for a moment and the cars gave me a purpose for the act. They were small enough to be easily portable, yet large enough to be able to make interesting shapes and practice consistency to improve my skills since both sides of a car had to look the same. They were a great educational tool for my habit and I got the added bonus of racing them too. No wonder this habit had such a strong grip on me.

Many changes over the years have also affected the processes I used to create the cars that evolved as solutions to problems were explored and technological changes allowed modifications to a process that improved the product.

Life on the planet earth constantly proves that to survive, a species must constantly adapt to a changing environment, and those that don’t evolve become extinct. The simple process of taking wood off of a block with a pocket knife seems constant, but to improve racing cars by making them faster or creating more accurate depictions of historic cars, I not only had to improve my carving skills but change techniques to create a more accurately shaped blocks used to start the carving process; which corresponds to a better quality product in the end. To know and understand what changes were needed took persistence and an education dolled out over time.

The First and Last group of cars in the Stud section is a collection of cars that illustrate the story that represent the first and last of trends in the development of the process of carving cars over the last 25 years. This group of cars is what I believe to be the pivotal works in the development of the Rollo’s Racing Barn Collection and changed the way I made future products after these special cars established the change in the process. The project and the changes they produced are listed below.

The first car in this group is the Toad Special. This is the first Pinewood Derby car I ever carved and established the habit and love of carving cars for me. The Toad Special was made from the Pinewood Derby car kit and began the quest to create the faster, more durable race car.

The second car in the group is the Porsche 911 made from a piece of Cypress wood that was a scrap from the construction of my parent’s house. This is the car that began the exploration of making cars from hardwoods with fenders to cover the wheels. Many obstacles had to be overcome for this car to make it down the race track.

The third car is the 1984 Ferrari Testarossa made from Wild Cherry wood. This car was one of the famous “Twin Cherry Ferrari’s” that I raced in the McIntosh city races as a revenge car against one of the fathers in the Cub Scout Pack. This car was the last car I carved where the emphasis was on the smoothness and finish of the wood.

The fourth car in the group is the 1987 Ferrari F40 made from the same block of Wild Cherry as the Testarossa. This is the other “Twin” was also made as a revenge car and it dominated the McIntosh city races that year. This was the first car where the emphasis was on the carved details of the car.

The fifth car in the group is the 1959 Chevrolet Impala carved from a piece of aged Oak I had saved for years. This car was made as part of a series known as “The Fins” which featured cars made in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s that incorporated large fin shapes in their designs. This car was made as an artistic automotive sculpture with a concentration on the fine details of the car, but I found a serious flaw in the proportions of the car which forced a change in the pattern making process. Cars up to this time were made with patterns based on a visual observation of a picture of the car and I found it allowed inaccurate proportioning of the form. This was one of the last cars to use that pattern making system and started the search for a new system to make patterns to construct the cars.

The last car in this group is the 1966 Pontiac GTO made from a cedar board I bought at Lowes. This car is the first car made utilizing the computer program I developed to create the size of the pattern used to make the cars based on the dimensions of the actual car. I had problems in the past with cars that did not have the right proportions and found that my problems were directly related to problems with the pattern I had used to make the car. The GTO was a mid-sized car with a square-shaped design I used for the testing of the program to see if it produced dimensions to make more accurate representations of the real cars and changed the way I had produced the cars since I began carving them.

These First and Last cars represent some of the major developments I made to the process of making racing cars and historic automotive sculptures over the last 25 years. The most significant change to my process has been the shift from making racing cars to historic automotive sculptures with the closing of the Pinewood Derby track. Finding a new direction for your dream is always tough. Several times as I have created these special cars, I felt that I had created the perfect car and thought I could do no better, only to discover that the next car I made looked and ran better than the car I thought was ‘perfect’. There will be more changes to the sculptures as the process of making the cars continues to evolve either based on development issues or changes in technology. As long as the desire to create is burning in me I will continue to create automotive works of art from some of the most exotic materials and the best methods available to me. Please take your time and enjoy the tour of the Studs barn and learn how simple ideas and technological changes advanced a dream that is still evolving through time. Rollo

The Toad Special

In 1982 I was living in a Victorian time warp of old brightly painted wooden houses nestled under the shade of large Live Oak trees draped with Spanish moss in the middle of north central Florida. On the night of December 11, my pregnant wife’s water broke and we began an ill-fated attempt at a home birth. I was nervous about the ordeal and needed to call the mid-wife for the delivery, but I had to go next door to borrow a phone because there were only so many phone lines in the town of McIntosh at that time. I had been informed that the town had 441 residents and I had to wait for someone to die before I could get an extension. The home birth phase lasted 24 hours before we gave up and went to Alachua General Hospital. In the early morning hours of December 12, at 2:30 AM, I found myself at the business end of the birth process in an emotional state somewhere between ecstasy and scared to death. When my daughter emerged, I was there to catch her, cut her umbilical cord, and watch her take her first breath. As I held her in my arms she began to cry, making her arms and legs twitch nervously. I cried, “Look, she looks like a little toad was born”. Toad became a term of endearment that I use for her still.

I went to church across the street from my home in McIntosh and I met a man who was the head of the Cub Scout pack in town. Ross Rath was a thin white headed man with more energy than a two year old although he was in poor health. Ross suffered from emphysema and had trouble walking since he was stooped over due to back problems. Ross’s breathing issues were so bad that he had trouble walking across the sanctuary of the church and had to stop and take a breath before he made it across the room, however, this man kept the Cub Scout pack going for the boys in town since few people would volunteer to help him. I asked Ross why he continued to work with the kids when his health was so bad and he told me, “If I can just save one boy from a life on the streets, just one; it will have all been worth it”. Ross told me he needed help to set up and run the Pinewood derby races that year and asked if I could help. I said I would, and Ross said he would give me a car so I could participate with my daughter in the city races held after the Cub Scouts have their race. Ross brought me a Pinewood Derby kit to church the next Sunday and I began to think about what to do with it to make a race car.

I had not seen or heard of a Pinewood Derby car since I was a Cub Scout myself. I remember building a car with my father, which turned out to be one of the few things that we would ever do together. I remember my father cutting out the body of the car with his pocket knife. The car shape looked like an old open wheeled racer from the thirties, and we found dark blue paint in his shop in our garage to use on the car. I remember that we did not have a paint brush so Dad took a small limb off of a Dogwood tree in the back yard and used his knife to splinter the end where it made a crude brush that looked more like the end of a mop. We painted both the blue body and the silver highlights with that brush and Dad had found some varnish we applied for a clear coat. Dad added some tacks to the front for headlights before we took the car to the races. The car ran well, but it did not bring home any ribbons, however it gave me a memory that has lasted a lifetime.

Ross gave me my first Pinewood Derby race car to build as an adult, however I had never thought about carving a car before. I had carved balsa wood with an Exacto knife in college for an art class I took on three dimensional design, and I found I liked carving wooden sculptures. I thought the idea of carving my own race car would be fun so I began to research a car design since I only had a month to create this car and I was a very busy man.

I knew nothing about what it took to make a fast race car but I had the idea that for the car to go fast I needed to control the friction the car would encounter. I thought of an old physics class I took in high school and I thought I wanted to increase the lift and decrease the drag on the car by making a shape like an aerodynamic airplane wing. A man that I carpooled to work with had an old airplane design manual that he let me borrow and I started sketching designs based on an airplane wing shape. The car looked more like one of the modern art sculptures I had done in college rather than a race car. The front of the car rose high over the front wheels but narrowed at the top and the back of the car was wide and tapered toward the ground with a flip tail. Once I drew the shape I liked, I drew images of the car on an index card and cut out the shape to make a pattern. I put the pattern on the block and traced around the edges to transfer the design to the block. I used the design for guidelines and cut out the car by hand with an old Bokker pocket knife that I had been given by my grandfather. The pine wood that the car kits are made from is a little soft, hand picked for straight wood grain, and easy to carve so the older kids who try to car the car themselves find they are able without too many problems.

I had another idea to convert potential energy into kinetic energy by putting the weight in the wheels so the car would gain speed as it went down the track. (I later learned that this was not allowed.) To accomplish this I thought of using small BB’s and mixing them with wax, and pouring the heavy mixture into the inside of the wheels. The wheels are open on the back side and would hold the mixture. I thought if the wax and BB’s did not stick out past the edge of the tire that the idea would work.

After I carved the car and sanded it smooth, I painted the car lip-stick pink with purple sides. I gave the car several coats of clear coat to make the cars look like it was made of shiny plastic. I took the car to work with me and weighed the car on one of the scales at the lab and added the weight needed for it to meet the specifications for the race.

The night of the race was a very exciting time with all the kids from the small town at the meeting to race their cars. Ross had always let any kid who wanted to race a car come down and race their car after the Cub Scouts had finished their official race. This was known as the City Race and it was a popular event in the small town. As I was working the race, I noticed some of the older kids were hiding their cars in their jacket pockets so no one could see their specially built cars. After the Cub Scouts finished, the beginning of the city race was announced, the kids ran to the starting line for a chance to race their cars. Some kids would try to manipulate their place in line so they could race against their friends, while others were happy just for the chance to race their cars.

I left the race car I had made in a box so my daughter would not damage it. However, once the city race was announced, I let Kate take the car and get in line to race it. She was dressed in a pink shirt and jacket with purple pants to match the colors painted on the car. She was the fourth person in line and she was very excited. One of the Cub Scouts who was participating in the city race asked Kate if he could race her car, and she accepted. They gave their cars to the staring judge to place on the track and the two kids went to the finish line to watch their cars race.

The Pinewood Derby track is approximately thirty-feet long and is separated into two sections. The first part of the track is a long sloping section about 15 feet long where the track descends approximately 4 feet to the floor. Then there is a gentle transition to the 15 foot flat straight section that runs all the way to the finish line. At the top of the track is a section where the cars will sit and a pin comes up through the bottom of the track to hold the cars in place. When the race is signaled to start, the starting judge will hit the starting bar which is attached to the starting pins. This causes the pins lower beneath the track allowing the cars to head down the track under the pull of gravity. The race is run by each car racing on both lanes of the track to determine the winner, and if there is a tie, the cars race the final race on their original lane.

When the beginning of the race was announced, the starting bar was hit and the cars shot out of the starting gate. Kate’s car ran as I had thought; The Toad Special started slowly but built up more speed quickly as it ran down the track, since the weight was in the wheels. The Toad Special raced past the other car at the bottom of the hill and kept increasing in speed as it raced to the finish line. The Toad Special won the race by three car lengths. Kate was so excited that when she picked up the car at the finish line and turned to take it back to the starting gate to trade lanes and race again, Kate dropped the car and it flew in the many pieces. We tried to get the car back together so she could race again, but the weight had come out of the wheels and the axles came out of the block so the car could not race again that night. Kate was so upset, that I had to take her home and come back to finish helping with the race. As I walked back to the McIntosh Civic Center, I began to think about what it would take to make a car with closed wheels so the cars would be more durable and not fly apart again.

The Toad Special raced again the following year. I had volunteered to help with the race once again, but I did not have time to carve a car, so I decided to use the Toad Special again. I had to go through some of the boxes I had in my closet to look for the car. However, when I found the car, it had to be totally reconstructed. My wife had given the car to my son to play with while he was teething. Miles managed to chew the flip tail off of the car and lost a wheel and axle. I had to carve the back of the car again, which changed the design by making a shorter tail.

The car had to be repainted since Miles had eaten the tail down to the bare wood. I did not have any more of the pink and purple paint to return the car to its original color, so I found some paint around the house and painted the car white on the top and blue for the bottom. The car was rebuilt in time for the race and Kate returned to the City Races at the Civic Center for the racing event. The car ran well, however the car did not perform as well as its initial race. Kate won many races through out the night but the car was 5th overall at the end of the racing.

This was the first Pinewood Derby car that I had built to race and the experience was wonderful. Carving that first car for me was like smoking your first cigarette or drinking your first beer: once you feel that rush of excitement and get that buzz, you crave more and make plans to do it again. The habit was established. I did not notice it myself but my boss had. I carved the Toad Special at work during breaks and my lunch time since my life at home was crazy with young children and an un-supportive wife. My boss always cruised around the lab looking for people wasting time and he saw me carving and said, “So I see you are carving cars now”. I thought to myself that carving this car was a one time event, but I found that carving was a relaxing escape for me from the hectic insanity of the asphalt testing lab for the state of Florida where I worked.

After several years of racing I learned that it is best to build a new car every year since the cars get abused during the race and trying to keep all the parts together for a year can be challenging. Later I learned that the axles will corrode in the high humidity of swampy Florida which creates friction with the wheels that slows down the cars so older cars normally do not run as fast. The next year I built two cars for the City races because my son, who ate the tail end off the Toad Special, was old enough to go and participate in the races. The Toad Specials major influence on my carving was to establishing the habit of carving in my soul where it started the creative juices flowing. I still had my idea to build a hardwood car with covered wheels, but it would be another two years before I attempted to create it.

Porsche 911

In 1931 Ferdinand Porsche founded a company that specialized in motor vehicle development work and consulting called “Dr. Ing. h. c. F. Porsche GmbH”. The office was in the center of Stuttgart Germany, and they did not build cars under their own name. One of the company’s first assignments was to design a “people’s car” for the German government that resulted in the Volkswagen Beetle. During World War II, Ferdinand Porsche became Chairman of the Board of Management for Volkswagen and most of the Volkswagen production was utilized for military projects. At the end of World War II, a British major became in charge of the Volkswagen plant and Ferdinand Porsche was arrested for war crimes, however, he was never tried. Ferdinand’s son Ferry took over the company until his father’s release in 1947. Ferry decided to build his own car because he could not find one that he wished to buy. These first cars were built in a small saw mill in Gmünd Austria. The prototype was shown to dealers and once a set number of orders were placed, production began. Car parts in post war Germany were in short supply so the 356 used components from the Volkswagen Beetle. The 356 was road certified in 1948, but continued to go through several evolutionary stages named A, B, and C, where Volkswagen parts were replaced by Porsche made parts. The last 356’s were classic Porsche designs consisting of a well balanced car and the first Porsche designed air-cooled engine in the rear. The body work was designed by Erwin Komenda, who had designed the body of the Beetle. In 1956, it became evident to Ferry Porsche that he needed to create a new car to replace the dated 356, which was small and underpowered compared to other sports cars produced at that time. Various models were designed but the true sports car concept remained, and the world famous ‘Porsche shape’ would be retained. Ferry believed that front engine cars were not competitive enough on a long term basis, so the rear engine design was retained. In 1959, Ferdinand “Butzi” Porsche made the original drawings for the 911 model which was larger with more comfort and featured a larger more powerful motor. The car was styled by Butzi, and Erwin Komenda, who headed the Porsche body construction department. The 911 preserved the general shape of the 356 but improved the aerodynamics. The rear engine layout created a weight bias toward the rear with the weight distribution at 40/60. Porsche felt this would help make the steering light and responsive while avoiding any artificial feeling produced by power steering boosters. The new design made luggage space a priority over the suspension, utilizing struts in the front and semi trailing arms in the rear to save space. The design phase of the 911 caused internal problems with Komenda. Butzi complained Komenda made unauthorized changes to the design and Komenda was demoted before the car debuted. The car was originally designated as the Porsche 901, and 82 cars were built before Peugeot protested the name. Peugeot had exclusive rights to any car name with three digits and a zero in the middle. Porsche changed the name to 911 as a result. The car made its initial debut at the Frankfurt Motor Show in 1963 with a non-functioning 901 engine that was replaced in February of 1964. The initial reviews praised the car; with one review calling it one of the best Gran Turismo cars in the world. As glowing as these reports were, Porsche had problems with the original car and continued to develop the car during its production run. Rear-biased cars always have a problem with handling since the cars have a tendency to oversteer, which can cause a loss of control. The suspension set up had to be accurately tuned to correct the problem, but the strict tolerance required could not be implemented on the production line. The first solution was to add two 11 kg cast iron weights to the front bumper, officially called ‘bumper reinforcement’. Engineers moved the location of the strut and the weights were removed in later models. Wider tires were utilized in 1969 along with stretching the wheelbase a few inches which greatly improved handling. The aerodynamics improved as well. In 1972 the ‘duck tail’ spoiler was introduced on the 911 RS. It reduced rear aerodynamic lift by 75% and improved high speed stability. A year later a bigger ‘whale tail’ appeared on the RS 3.0 and was used on all other cars because it eliminated rear lift. The Porsche 911 became a cultural icon of ‘60’s cool’ as soon as it went on the market. The car segued into becoming the icon of performance in the 1970’s. In the 1980’s the Porsche 911 became the icon of sophistication and influence. In the 1990’s the car was know for athleticism and power. Today the car has evolved into a symbol for quality and performance. The British television show dedicated to testing sports cars called Top Gear said that when you consider price performance, economy and emissions, that the Porsche 911 is the worlds best sports car.

When I decided to carve the Porsche as my first car to make a ‘hardwood’ derby car, I did not think about the historical significance of the car. I had an idea to make a Pinewood Derby race car with fenders to cover the wheels so the car would be more durable when handled roughly by the kids. This is the first car I created that explored this idea. I had no idea about how to cut out the wheel wells of the car while leaving the body intact. Pinewood Derby car kits have exposed wheels and a groove is cut in the block to set the axles so the wheels remained square. My first thought on how to make a car with fenders to cover the wheels was to make a car in three sections: with a center body section and two individual fender sections. The car required that the wheels were parallel and perpendicular to the body so the car would roll in a straight line. The idea was to drill the holes for the axles in the square center section of the car and simply add the fenders to the sides later. The Porsche 911design would allow me to do that since the shape featured wide sides and flared fenders. I thought about the car for several weeks before I attempted to carve it. I took a trip to visit my parents and found a piece of scrap cypress wood leftover from the construction of their house to make the car. This cypress wood used on their house was cut at the turn of the century when the loggers had gone across the state cutting the virgin timber and floated it down the various rivers to a temporary saw mill set up to exploit this trade. Many of my relatives were involved in this profession. Some of my relatives had known where some of the wood had sunk in the middle of the Apalachicola River seventy-five years ago, and they found it and harvested it. My father had used this wood to build his new house. The cypress wood had a nice golden color and the grain was very straight. I took the wood home and managed to find a coworker named William Lloyd. William let me cut out the pieces for the car on his band saw during our lunch breaks from work. I did not own any woodworking equipment and I always had problems finding equipment to use in the past. I always cut out the shape of the car first because I thought that was the hardest part of the process. I wanted to make sure that I created something I could use to make a car before I tried to do something else to the wood block. Cutting out the car shape first made holding the car flat challenging to keep the body square to drill the axle holes. However, it would take years for me to break the habit and begin drilling the axles and wheels before cutting out the body shape while the block was still intact.

I had no woodworking skills when I cut out the sections for the car, and they looked terrible. I used an old Bokker pocket knife that my grandfather had given me to whittle the form and make the fender sections. The car looked rough at best. Another idea William and I had was to make inlays of hard wood for the wheels to run against to reduce the rolling friction of the car and increase the speed. A friend gave me a piece of scrap wood from his living room floor called Cumaru wood from Central America. This wood was dark brown and very hard. I used a dado blade on the table saw to cut out a trench and I installed the Cumaru wood inlays. The fender sections of the car looked awkward when the pieces were cut out. I had no others and carved them anyway. I drilled holes for the axles through the hardwood inlays even though the block was no longer perfectly square. Once the fender sections were glued on the car, I began to sand the car for a nice smooth finish. I tried to get the car as smooth as possible for wind resistance and appearance. The golden color of the cypress wood looks good but it does not make a smooth deep finish by simply sanding it. I found it took as long to sand the car as it did to carve the car. I found some bees wax at work that was used to coat forms on concrete specimens and I hand-rubbed the wax into the wood. To my surprise the grains of the wood began to shimmer and shine. I was hooked on the natural finish from that moment on. The lovely gold colored grains in contrast to the rich brown wood made the car glow. The cypress is not known for a highly polished look when finished, but the Porsche had a nice satin shine that made the car look great. The process of putting the wheels on the car looked easy enough, but when I tried to roll the car, it would not roll in a straight line. The wheels rubbed against the edges of the fenders slowing the car down. I had to take the wheels back off the car and whittle down the inside of the wheel wells so the car would roll with out the wheels rubbing. This is the reason the wheel line of the inside of the fender is not smooth. I finally cut enough wood away so the wheels would spin, and I thought I had solved the problem and I glued the wheels back on the car. I learned that it took as about long to get the wheels on the car as it did to carve it. I finished the car with only two days left before the race. I had made another car at this time using a different idea of how to make a car and I developed the two cars together. William had discovered a key hole saw after we had made the Porsche, so the other car was made in one piece utilized the key hole saw to make the wheel wells. This car was made from a piece of West Virginian Cherry that a friend had given me to carve since I had trouble working the cypress. I carved a Cobra from that wood and that car will be featured at a later time In the Studs section. I took the cars to work the following day and put them on one of the scales at the lab. I learned that the Cumaru wood inlays were heavy and now the cars were over the weight limit. This is a big problem since being over the weight limit could disqualify the cars. I was trying to make a car that would meet the official specifications while using hard woods, so I took the cars home that night and drilled out the insides from the bottom side.

The cars looked like a shell if you flipped them over. I managed to get them down within the specification limit, but now I had to be careful with every modification to the car to make sure that it did not add too much weight and disqualify the car for a weight violation. I had become the Cubmaster of the pack at this time and the following afternoon I went to pick up the race track at the home of Ross Rath, who had founded the pack and was the Cubmaster for over 30 years before poor health forced him retire. Ross had built the race track and kept it stored in his garage. I was proud of the two cars I had made and I took them to show Ross. Ross took the cars in his hand and he simply said “Wow” as he held the cars and turned them so he could see the workmanship and added, “I have seen many different cars carved for this race, but I have never seen cars like these. They are something really special”. They looked fantastic and they looked like nothing that had ever been made and raced at the McIntosh track before.

After taking a moment showing the cars, I went with Ross to the garage I loaded the race track into my car. I took the track to the McIntosh Civic Center and I set it up for the race that was to be held the following night. The track is 30 feet long and it was built in sections so it could be moved and stored easily. Once the track was together, it has to be polished and tested to make sure the cars would roll down the track with out any problems. The joints in the track have to be perfectly aligned so the cars do not hit a bump and try to jump or fly off the track. The track features a raised section in the center; between the left and right wheels of the car. This is why the specifications state the cars must be 3/16th’s of an inch high to accommodate this raise. The raise helps keep the cars from running into each other during the race if the wheels are not on the car correctly and the car does not roll straight. I took out my cars and tried them on the track to conduct the track testing and I was shocked and horrified. My car’s wheels were so crooked that the car kept rubbing against the raised section of the track and the friction was so bad that the car would stop on the sloped part of the track! I only had the next day to fix the problem because the race was to be held the following night, and I had to go to work the next morning. Some of my scouts were playing in the park and came inside to watch me set up the track and run the cars. When the cars stopped on the middle of the track, the kids laughed and said, “Those cars look neat but they sure do suck. They won’t even roll”. This was the first time I understood that it did not matter what the car looked like, it had to be fast to be popular. I went to work the next morning and talked to William about the wheel problem. William had an idea to bend the axes of the cars so they would roll straight. William thought it would work like regular car wheel alignment. We had no other choice since the car’s axle holes were drilled and the fenders carved. Drilling a new hole for the axle was out of the question because there would be no way to get the axle square with the curved sides of the body. I managed to pull the wheels and axles back out of the car, and then we bent them and replaced them in the car until the car would sit relatively flat on the desk and it would roll in a straight line when pushed. I also had to cut down the wheel wells more since the wheel alignment had changed the wheel position, causing the wheels to again rub against the side of the fender again. I used this bent-axle process on both the Porsche and the Cobra and managed to get them both to roll straight. I had no time to do anything else to the cars because when I left work at the end of the day, I just had time to drive home and go to the Civic Center and run the race. The day of the race is always exciting because the boys in the pack have been working on these cars for a month and they are ready to see them run down the track. The boys also love to taunt their friends and race each other for bragging rights. The more I raced the Pinewood Derby cars, the more I realized that the parents were more focused on the race than the boys in the Pack. The Cub Scouts always race their official race and give out their awards before any of the city racing begins. I had hidden my cars in a towel near my chair because I knew that my cars were very different and I did not want to have the kids focus on my work since we were here to celebrate theirs. However, once the city race was announced, my daughter and son took the cars to the starting line and they were ready to race. The first thing that I found shocking me was that there was no weigh-in requirement for the city race, so drilling out the car was not necessary. This was a big disappointment because I felt that I had done great harm to the cars by drilling them out and I never attempted to drill the cars to reduce the weight again. The cars turned out to be very fast with the wheel adjustments. The same kids that had watched the cars run the night before asked to race against the cars thinking that they would easily beat them. They were shocked. My son and daughter had a great time racing the two unique cars against their friends. The cars turned out to be very fast and they ended up winning every race. The cars turned out to be a big success and as I watched them race down the track that night, I thought how to improve the process to make a faster car.

In 1963 the world was focused on the spread of communism, new technology, and the space race. In the United States, the people were trying to come to grips with the fight for civil rights, the beginnings of the Vietnam War and the assassination of a President. While the automakers in Detroit were finding ways to stick larger engines in the front of their large square-shaped cars, Porsche had the vision and the fortitude to move forward with an original concept that was vastly different from other automobiles; where a small car had its little air-cooled engine in the rear that performed like the larger sports cars. Since its introduction in 1963, the Porsche 911 has undergone continuous development to either improve design issues or integrate new technologies to improve the car, while retaining the basic concept. The same can be said for the Porsche 911 that I carved as my first ‘hardwood’ derby car. The concept was created to search for a way to cover the exposed wheels of the Pinewood Derby race cars so the cars would be more durable if they were handled roughly. Although this first idea worked, I changed the process of making a car in three sections as soon as I discovered the key-hole saw and was able to cut the wheel wells into the sides of a solid block of wood. The development of the process I used to make carved hardwood cars continued as new technologies and techniques were discovered and modified to make the racing cars faster. When the race track fell silent as the Cub Scouts grew up, I quit making Pinewood Derby race cars and started creating wood automotive sculptures of rare classic automobiles to keep my carving habit alive. The challenges are different when making a sculpture because the emphasis is on the appearance rather than worrying about parallel wheels that make the cars roll straight and fast. I still constantly improve the process while relying on some of the techniques that I have learned from making these older race cars. I recently finished a Delahaye 175 S that has bulbous fenders and covered wheels on both the front and back of the car. The design required that I cut out a new side for the car and glue it over the wheels. As I was gluing and clamping the new sides on the Delahaye, I reminisced about all of the things I learned while creating this Porsche 911 over 25 years ago, and the problems I had to overcome before the car could race. I remembered how working through the problems of making that car and finding new solutions started the desire to create these cars in me. The collection of hand-carved exotic racing art now known as Rollo’s Racing Barn continues to display the evolution of the original concept.

1984 Ferrari Testarossa

In 1982, Pininfarina was commissioned to style a 12-cylinder Ferrari with radiators mounted in the sides of the car like a racing car. The vehicle was to be shaped in the wind tunnel to ensure adequate airflow to the rear mounted radiators, and effective air flow to the rear engine bay. The car had to accommodate luggage in an adequate storage space, provide extreme comfort and provide high performance as the top of the road car line for the world’s premier sports car manufacturer. The car was based on the Berlinetta Boxer, but the new car had to be faster, handle better, more spacious and luxurious that the outgoing Boxer and the car had to be legal in every country. The result was the creation of the most recognizable and influential car of its time.

The Ferrari Testarossa debuted at the Paris Auto Show in September of 1984. Ferrari had been building luxury cars since the 1940’s but the striking lines of the intakes on the exterior of the car caused Ferrari to gain momentum in the United States with this new ground breaking engineering. Ferrari had created this new style as a backlash against conservatism that had covered Europe and the Italian luxury car market during the 1970’s. Overall the reaction was polarizing with some people hating the design while others, including the market, loved the ‘outrigger mirrors and the ‘claw marks’ on the sides.

The body of the Testarossa was controversial because of the side strakes that were referred to as ‘cheese graters’ or egg slicers’, which spanned from the doors to the rear fenders which were needed for countries that outlawed large openings on cars. These side strakes were one of the most copied automotive styling motifs to come out of the decade of the 1980’s, and they were copied by both automobile manufactures and automotive styling houses that used the idea for years to give their cars the “Ferrari Look”. The strakes made the Testarossa wider at the rear than the front which increased the handling capabilities and the stability of the car.

The Testarossa’s look, performance and reputation made it one of the eighties ultimate status symbols. From its introduction in Paris in 1984, the Ferrari Testarossa remained at the center stage of the automotive world for eleven years as the world’s fastest regular production car. It defined the term ‘supercar and was the innovative benchmark against which all contemporary sports cars were measured. In 1992 the Testarossa ceased production after 7200 units were sold making it one of the most popular Ferrari models ever and established Ferrari’s dominance in the high end sports car market The Testarossa was replaced in 1996 by the front-engine Maranello 550.

The Ferrari Testarossa was the first of the ‘Twin Cherry Ferrari’s’ that I had created out of a single block of wild cherry wood that I had found in a friend’s garage. The Testarossa was one of the most coveted sports cars of its time, made famous by the scenes of the car racing around the streets of Miami in the ‘Miami Vice’ television series. This was the first car I had designed and planned to create as a ‘revenge car’ to race against the parent who had created the ‘Coffin Car’ the year before. The Coffin Car was made from a Pinewood Derby kit and it had all of the details of a real coffin and the professional paint job to go with it. The parent had sworn his son had created the car, and I decided to make a car as outrageous as the one he had made, and let that parent race against my car. The Testarossa design was distinctive and I knew that both the kids and the parents would recognize this car adding to the excitement it would generate.

Wild cherry wood is a beautiful red colored wood that is relatively easy to carve and it holds an edge well which allows the carving of small details. The color and iridescent grain of the wood make it ideal for the natural finish that I employ on my cars. The board I found was large enough to make two cars, and the F-40, (the other ‘Twin”) was created out of the other end of the same board.

I carved the Testarossa at the time when I was concentrating on making cars that illustrated speed with the shape of their design. I loved the design of the car because the low wide stance combined with the long sloping hood line gave the car the look of speed when it was stationary. The curve of the front fender and the way it bends to cover the front wheel and to meet the hood line combined with how this line runs back to form the rear door pillar are in contrast to the flat side intake that sticks out for the strakes making the design flow with a dynamic wedge look which emphasizes the low and wide stance of the car. The side strake helps emphasize the visual flow of this design.

I was more concerned about the shape of the form and making the texture of the car a smooth as possible during this period of my carving. I carved the strakes down the sides of the car for the distinctive ‘Testarossa look’. I sanded the car as smooth as I could by using #600 grit sand paper to give the cars an illustrious finish when the bees wax was applied. The bees wax really brought out the fine grains of the wood. Many of the small details of the car were sanded down in order to accomplish the super-smooth finish, but the distinctive shape was enough for everyone realize what type of car it was.

On the night of the race, my son Miles and my daughter Kate were more interested in racing each other than racing anyone else. They had watched the development of the cars and both kids had chosen which car they wanted to race. Kate had chosen the Testaroosa and Miles loved the F-40. The childish banter had started weeks before the race with each child expressing superiority over the other child’s car made their mother sick of the event by the time of the actual race. My children knew the kids they were going to race against before we walked into the Civic Center, but the rivalry between the brother and sister racing the twin cherry Ferrari’s against each other was the race to watch that evening.

My daughter Kate took the Testarossa to the race track and she raced many of the other cars at the track that night. The Testarossa proved to be incredibly fast and beat the other cars solidly. Kate was proud of her car and raced it as many times as she could because it beat the other cars so easily, and she was proud. The Testarossa would jump out of the starting gate quickly and just keep accelerating down the track. The car had so much momentum at the bottom of the track that it would actually gain speed all the way to the finish line leaving the competition at least three car lengths or more behind at every race she participated in.

The big race of the night was Kate and the Testarossa racing against my son Miles with the F-40. The two cars were built with in the Pinewood Derby specifications, but the two cars looked menacing at the starting line since they were so low to the track and both cars looked wider than the normal Pinewood Derby car from the kit because of the wide body that covered the wheels. The kids at the City Race became quiet as the cars prepared for the start of the race. All the kids in the room were as eager to see this race since they had heard about these cars on the play ground, and now they finally were able to see the cars and watch them race. When the judge shouted “go’ and the starting gate dropped, the F-40 jumped out of the block and took off down the track with the Testarossa right behind less than a half of a car length, but the fast speed of the F-40 at the start was too much for the Testarossa to over come, and the F-40 was the overall winner of the day. The two cars raced many times that night however the F-40 won more times and was announced as the victor. Kate was upset that her car did not dominate her brother’s and she went home early from the race, leaving me to pick up the cars and close up the civic center by myself that night.

The twin cherry Ferrari’s went down in McIntosh history that night as the special cars of the city race. The two cars raced again the next year, but I had produced other cars to compete in the races for that year. The excitement of racing new cars always takes precedence over the rerunning of the old ones. The Twin Cherry Ferrari’s were returned to their box in the top of the closet until they came out for this display.

The Ferrari Testarossa was the last car I carved with the emphasis on a smooth ‘mirror like’ finish to the detriment of the finer details of the car. The carved Testarossa had to be the best and fastest car I had ever made to compete with the super cars the other scouts were building, which was similar to the challenges facing Ferrari’s development team when they created the original car. All of my resources were put into this project, and like the real Ferrari Testarossa, the race car won the day with both speed and execution of the innovative style. The next car I carved was the Ferrari F40, and it would point my carving in a new direction with more details carved onto the body’s surface. I was becoming a more skilled carver and I was better able to create the details. The move to make more detail cars began the trend of the cars becoming more like artistic replicas of famous cars and less like true race cars, which is a movement that would eventually dominate my carving of cars.

Ferrari F40

In 1985 Porsche caught the attention of the world at the Frankfurt Auto Show by demonstrating a new supercar prototype called the 959. This new car was powered by a 450hp twin-turbo flat six engine and had 50 more horses than Ferrari’s top supercar at the time, the 288 GTO. The Porsche 959 had a top speed of 197 miles per hour, making it the worlds fastest car, and beating the 288 GTO by 10 mph. The 959’s sophisticated electronic-controlled 4-wheel drive system and advanced suspension with adjustable damping and ride height suddenly made Ferrari’s 288 GTO seem second rate. Ferrari’s general manger Giovanni Razelli stated “The fastest road going sports car has to be a Ferrari” and he planned for the development of an even faster car to compete against this new Porsche. The plan was simple: create a vehicle that combined the company’s best technologies into a no-frills sports car that would come close as possible to being a full fledged race car while still retaining the necessary equipment to be a street legal product. Ferrari had begun development in 1984 of an evolution model of the 288 GTO intended to compete against the Porsche 959 in FIA racing’s B group. FIA brought an end to the B Group series in 1986, which left Ferrari with five 288 GTO Evoluzione cars with no where to race. Enzo Ferrari had the desire to make a final supercar to leave as a legacy, so these cars were developed further for road use. The car was to celebrate Ferrari’s 40th anniversary of the car company and it was to be the last Ferrari automobile personally approved by Enzo Ferrari himself.

The body was an entirely new design by Pininfarina studio and supervised by Leonardo Fioravanti. The unique styling made the car look like a race car complete with a massive air dam and skirts, widened fenders, rear diffusers, and lots of NACA ducts along with various ventilation holes stuck all around. The most spectacular feature of the body was the large square spoiler that integrated perfectly with the rear end of the car. Pininfarina had successfully integrated stunning looks and great aerodynamics in one car. The car utilized Kevlar, carbon fiber and aluminum for light weight and strength. Weight was reduced further by the use of plastic for the windshield and windows. There were no door panels, door handles, carpet, glove box, sound system, carpet or trim on the interior. The hallow doors were pulled shut by a simple cable. The first cars had Lexan windows that slid to the side to open. The steering and brake systems were non-assisted to save weight. A thin sheet of cloth covered the transmission tunnel and dashboard. The car used Ferrari’s Formula 1 composite material for the chassis consisting of a light weight carbon fiber/Kevlar/Nomex weave. The F-40 shape developed by Pininfarina was designed with aerodynamics in mind to reduce frontal area, drag and lift and smooth air flow. However, the primary concern was for high speed stability and cooling the forced-induction engine rather than terminal velocity. The car was like an open-wheeled race car with a body. Lift was controlled by spoilers and the massive squared-off wing.

The body was primarily shaped to optimize down force and drag and it generated real downforce at speed which was crucial to its superior track performance. The engine bay was covered by a Lexan cover to display the twin-turbo V8 engine. The body/chassis unit was fabricated by Scaglietti and finished at the Ferrari factory. The F40 had none of the Porsche’s sophisticated technologies. The car was built in classic Ferrari style and close to a formula one race car. The mid-engine design guaranteed a 50:50 weight distribution and the power went to the tires in the rear. The light weight, low center of gravity and perfect balance set the F40 apart for its German competitor. Ferrari named the car the “F40” to celebrate the 40th years of the Ferrari automobile.

On July 21st, 1987, at a press conference called outside the Ferrari factory in Maranello Italy, the 89 year-old Enzo Ferrari stood before a large group of invited dignitaries and special guests along with the world’s best automotive journalists to debut the car that was named to honor the forty years of Ferrari automobiles. Enzo spoke through an interpreter and said “A little more than a year ago, I expressed my wish to my engineers to build a car to be the best in the world. That car is here today”. At that moment the red covers were swept aside to reveal the automotive masterpiece that set the standards by which all other cars would be judged.

Enzo gave a speech praising the F40 and went on to draw references to the days when street cars could be raced on the track. Enzo Ferrari died on August 14th, 1988. The F40 was the last car that he would present to the world. Ferrari unveiled the F40 at the Frankfurt Auto Show in 1987 causing a stir in the crowd when the top sped of 201mph was confirmed and Ferrari took the title of ‘the worlds fastest production car’ back from Porsche. Although the show was held in Germany, the spectators were pleased to see Ferrari retake the title. However, the car costs twice as much as the Ferrari Testarossa, and the price continued to inflate before the car was delivered in 1988. Ferrari originally planned to only build 400 of the F40 cars, but so many people came with cash in hand that eventually 1311 units were built in four years with speculators paying three times the asking price to get their hands on the car. The F40 was discontinued in 1992 and in 1995 the F50 was intended to be the successor in GT1 racing. However only three racing F50 were ever produced and none of them actually competed in a race. The famous BBC car show named “Top Gear”, which tests and rates exotic supercars, refers to the F40 as the “greatest supercar the world has ever seen. The shows host Jeremy Clarkson went on to proclaim that the “F40 is one of the most beautiful cars ever made”. The F40 was the fastest, most powerful and most expensive car that Ferrari sold to the public at that time.

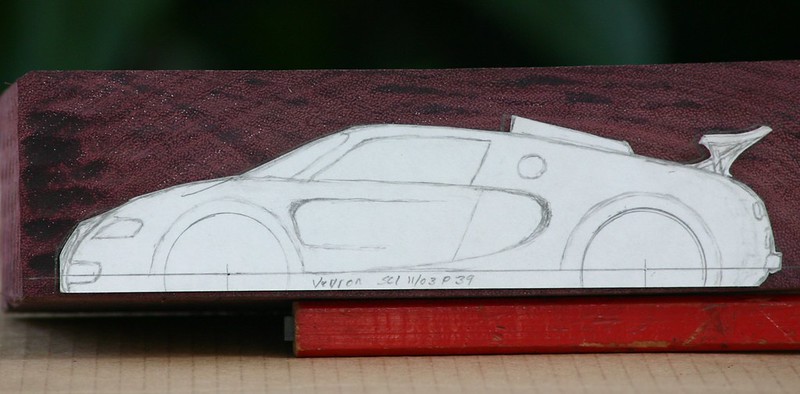

I made this car for that reason. The F-40 was part of a set of cars that I created; with the other car being the Ferrari Testarossa. Both cars were made from the same Wild Cherry log that I had found in wood pile at a friends house. I squared the log into a square board with a table saw and cut a car out of each end of the board. I created these cars in retaliation to one of the scout parents building an incredible Pinewood Derby race car that looked like a coffin with a mad man at the wheel the year before. The sides of the car were shaped like the edges of a coffin and similar to the shape of a body where the car was wider at the shoulder area and tapered at the head and feet. The coffin’s edge was highlighted with a small gold strip around the edge, similar to a real coffin. The end of the coffin where it was tapered for the head had the words ‘The End’ written by a spider making a web, all perfectly executed. The work was flawless, but any one knew that a 9 year old kid had not created this car. I asked the father of the child if he had built the car, but he swore the child had done all the work. I knew different and I plotted to do the same thing to him. The F-40 was the most detailed car I had carved to date. I had done a very good on the shape of the car and I carved out the many intake scoops that were found all over the body. I even carved the ‘F-40’ logo on the side of the spoiler. The iridescent glow of the natural cheery wood made the twin cherry Ferrari’s shine like no other cars at the race.

The fascination with getting a smooth finish was not so much of a concern for me with this car since I was concentrating on getting the details correct and I did not have as much time to work on this car. I managed to carve the numerous scoops and carved the “F40” logo on the side of the spoiler. This was the first car that I had carved where I was concerned more with the details of the car rather than concentrating on getting a super smooth finish. This car started a trend that would become more dominate in my carving style. I sanded the F40 smooth and buffed the finish to a shine, but not enough to erase some of the minor details as I had done with the Testarossa. The Cub Scouts held their race that year and I had brought my kids over to race in the City races at the end of the evening as usual. The father who had created the coffin car the year before was back with another finely made car. This time he had created an old 1930’s racer with beautiful flames painted on the sides. His son had raced the cub scouts and the car was fast, winning the Cub Scout races that year. The kid knew about the twin cherry Ferrari’s from playing with my kids at the park, but he had not seen them. I instructed my kids to leave their cars in the box until all of the scouting events were completed. This was the scout’s night, and we were just there for the races held after the scout event was over. I did not want to take away the focus from being on the Cub Scouts and the cars they had made for their races. When the City Races began and the F40 began to race, it was very exciting. The F-40 turned out to be incredibly fast and was unbeatable; winning all of its races by at least 5 car lengths. The man’s son who had the 1930’s racer was excited and wanted to race the F-40 as soon as he saw it. We arranged a race between the two cars. The F-40 turned out to be much faster on the track and beat the roadster by a considerable amount. The father went down to the end of the track and picked up the F40. He was amazed at the F-40 and began to complain that a child had not built the car and it was not fair to the other kids. I replied, “Just like your son built the coffin car or painted those nice flames on your 1930 racer”. The man became upset and picked up his car and his son and left for the evening.

The truly big event was the race between the twin cherry Ferrari’s. My son Miles raced his F40 against older sister Kate with the Testarossa in one of the most memorable races that has been held at the McIntosh track. The two cherry racers shinny finish glowed under the lights. When the signal to start the race was given, the F40 shot out of the starting gate and began to eat track at a pace the Testarossa could not handle. Kate and the Testarossa had won all of their races that night except for the main race against her arch rival and little brother. Miles was ecstatic and began to race every car that would line up against him, and he won every race. The car turned out to be so fast that some of the scouts would place their car on the track in front of the F40 and see if the F40 could catch it. It always did. At the end of the night, the front of the F40 was scared with paint streaks from the cars the F40 had pushed down the track. These racing badges of honor can still be seen on the front of the car today. The F40 raced again the next year and did well, but the kids were more interested in racing the new cars I had built. The F40 went into a box after that race and into my closet. It remained until the building of the racing barn, where it will be on display and remembered again.

After the race that year, as Cubmaster of the Pack, I thought of a way to try to get the fathers out of the Pinewood Derby Racing and leave the races for the cub scouts to enjoy. I learned the parents through the years had been involved in more altercations than the kids over the race results and I thought of a way to change this. I started giving the father’s a car to build and race the next year. I also made awards to give the fathers who won the day with the car that they created. This turned out to be a popular event and lasted until the Pack finally folded. The kids enjoyed the fathers participating in an event similar to theirs and there were several father and son teams that took home both trophies the same year. As time went on we saw less ‘father only’ built cars at the races, and the kids had a more enjoyable time. The F40 was the first Pinewood Derby Race Car I had created where I emphasized the details that were part of the design of the car and I did not concentrate so much on the smoothness of the body. This was a trend in my carving that would become more influential as I continued to carve cars. I no longer spent days sanding a car until it had a mirror like finish. I sanded and buffed the car so the grain would stand out, but not to the point of loosing the details. Both the real F40 and the Cherry F40 were created out of revenge. Both cars had to be executed in a short amount of time, and both cars had reputations riding on their success. Both cars required a complete effort to produce a car that was to be the fastest in their arena of competition and both won the day with their execution and speed.

1959 Chevrolet Impala

The 1950’s was a decade of great change. As the economy grew after World War II and consumers became more affluent, the automobile industry began to improve and redesign their products in an attempt to attract new customers and exploit this new source of wealth. Automotive stylists began to take their influences from the transportation industry with planes and trains used for their design ideas. The advent of the jet age brought technological changes and design breakthroughs in the production of automobiles so new car designs featuring compound forms and curves could be created at a faster pace. As the decade progressed, designers exploited the ‘jet-set’ lifestyle changing to styling motifs that were influenced by jet parts and modern streamline shapes. The 1950’s became known as the “era of the dream car” as customers demanded increasingly flashier and more powerful cars with more chrome and the industry provided them. Chevrolets were popular in the 1950’s because of their dependability, but lacked a sense of style or aesthetic appeal and they set out to change that. In the beginning of the decade, they offered the same body styles offered at the end of the war with little change. Designers created the revolutionary ‘hardtop’ design that looked like a convertible by omitting the “B” pillar and even though 1953 Chevrolet’s were advertised as cars that were “entirely new through and through,” but the reality was the cars were the same as the 1949 models with restyled body panels and a curved windshield. The hardtop cars with their less rigid structure required heavy reinforcement to keep the car from shaking. The real change came in 1955 when Chevrolet introduced the famous small block V8 in the Bel Air coupe with the ‘shoebox design’ featuring streamlined fenders, a small Ferrari inspired grille and more chrome. The light weight car dominated both circle tracks and drag racing strips thrusting the company into competitive motor sports. The car was redesigned again the next year for the ‘speed line look’ featuring a longer squarer shaped front end with a wider grille and redesigned wheel openings. General Motors executives wanted an entirely new car for 1957, but production delays forced the 55-56 design to be utilized for another year. Ed Cole, Chevrolet’s Chief engineer dictated a series of changes to the 1957 Bel Air increasing the cost of the car significantly. These changes relocated the air ducts to the chrome head light pods, a wider grill and straight tail fins to emphasize the car’s width, and they changed to 14-inch tires gave the cars a lower wider look creating the classic design. The larger 283 cubic inch motor and light body gave the Bel Air such a dramatic advantage when racing that NASCAR put restrictions on the car. Although the 1955-1957 Chevrolets moved away from the conservative styling of the past, the Bel Air model was not a successful as General Motors had hoped. Ford out sold Chevrolet for the first time since 1935 partially because Ford had also introduced new body styling featuring cars that were longer, lower and wider that their previous cars. However the main cause of the sale shift was attributed to Chevrolet’s change to using tubeless tires on their new models, which the public did not trust. 1958 was a recession year but Chevrolet redesigned their cars again to become longer, lower, and heavier with the tail fins now becoming deeply sculpted rear fenders. Chevrolet also introduced the big block V8 with the 348 Cubic Inch engine as the Bel Air became the top model in the product line with styling similar to the other Chevrolet models. The ‘Baby Cadillac’ front-end design featured a broad grille and quad headlights, and these changes returned Chevrolet to the number one selling car of the year, beating Ford and the other General Motors divisions. Chevrolet first displayed a car named the Corvette-Impala at the 1956 General Motors Motorama car show. The Impala name was derived from the southern African antelope known for running at high speeds. The car looked like an elongated four-seater Corvette design and featured hard top styling however, this design was not known to have survived. The Chevrolet Impala surfaced again in 1958 as the most expensive full sized passenger model Chevrolet made. Both Chevrolet and Pontiac’s design teams under the direction of Clare MacKichan, established the dimensions and basic packaging for their shared ‘A-Body’ car in June with the first styling sketch that would influence the finished product. The design caught the eye of General Motors styling vice president Harley Earl, and seven months later, the design was worked out. The Bel Air Impala was introduced in 1958 and as the most expensive full sized passenger model Chevrolet made. Both Chevrolet and Pontiac’s design teams under the direction of Clare MacKichan, established the dimensions and basic packaging for their shared ‘A-Body’ car in June with the first styling sketch that would influence the finished product. The design caught the eye of General Motors styling vice president Harley Earl, and seven months later, the design was worked out. The Bel Air Impala was introduced in 1958 and positioned as the top of the product line. The Bel Air was structurally different from other Chevrolets with longer and lower styling. The Impala received special styling cues including a different roof line with a vent above the rear window, unique side trim, and triple tail lights housed in broad alcoves. Ed Cole, Chevrolet’s chief engineer defined the Impala as a “prestige car within the reach of the average American citizen.” The new Impala was a success and helped Chevrolet regain its position as the number one selling car for that year.

General Motors decided to redesign their product lines in 1959 to share body shells across their automotive divisions and as a reaction to Chrysler Corporation’s successful 1957 ‘finned’ designs. The Impala was radically reworked to ride on the newly designed “X” frame chassis with a longer wheelbase. The new Impala was longer, lower and wider than before and looked like nothing else on the road. The headlights were placed as low as the law would allow. The leading edge of the hood featured long horizontal ‘eyebrows’ and the controversial ‘cat-eye’ tail lights were under flat wing-shaped tail fins, that were second in size only to Cadillac’s. The Sport Coupe featured a shortened “flying wing” roofline and wrap-over back window to complement the new compound-curve windshield, promising a “virtually unlimited rear view”. The 1959 Impala was a bigger hit than the popular 1958 model with its fresh stylish design and became the best selling Chevrolet for that year

In the summer of 2011 I found myself at the edge of a paradigm shift from my personal decade of great change. After the Pinewood Derby track closed down, I moved from the Victorian time warp where I had lived for 15 years due to a divorce, and found myself looking for a new place to make the cars since I had no woodworking equipment, and buying the equipment was now out of the question. I had created a process for creating race cars that was now obsolete. One of the hardest things I have had to deal with is knowing what to do when you get to the end of your dream. Creating cars for the sake of carving no longer had the sense of urgency that building race cars did. There are no deadlines to meet, no requirements for the shape or size, and no goals to attain. I had to create a new purpose and criteria to judge my work. I loved carving wood cars and decided to carve rare historic cars that few people would ever get to see, and make them from exotic woods. I realized that I would need to buy this exotic wood and improve the proportions of the cars if the historic automotive sculptures I desired to create were going to the next level.

I had bought my first exotic carving woods in 2005 when a friend of my sisters allowed me to use his wood shop. Jerry was a furniture builder and made beautiful pieces for his home, incorporating exotic wood inlays in his work and he knew where to buy it. He gave me the name of the place where he bought his wood and I took the contact information. This was the first time I had bought wood to carve and I concentrated on getting woods with exotic colors that I could find. Once the wood was purchased and I had blocks prepared to cut out the cars, I drove back down to the Victorian time Warp to my old friend Dave’s house and used his shop. I cut cars out of each type of wood that I had bought and created a series I called “The Colors” because of the bright colorful woods I used.

I concentrated on carving these cars with as much detail as I could. After I had carved most of the cars in the series, I knew I needed to make new cars to carve, but I did not have the money to purchase more exotic wood. I met my neighbor across the street, and he had a drill press, a band saw and a table saw that he would let me use. So in 2009, I began to gather woods to make blocks to create cars at my neighbor Jim’s garage. I knew that the next cars I made would never race on a track and be automotive sculptures and I had ideas to make cars in series that related to each other in some way rather than make individual cars as I had done in the past. Once the blocks of wood were cut, the next step would be to create the patterns needed to make the cars. The original process for making a pattern for a race car was simple. The Boy Scouts of America had created Pinewood Derby rules that set a limit on the size of the car. When I switched to making the first hardwood derby cars, I kept the same dimensions to keep the cars legal to race. Designing the cars was easy because I just had to draw the shape of the car in an 8 inch by 2 inch box. I did not have access to a band saw that would cut a three inch wide board at the time, so all of the cars met the width requirement when cut. I boasted that I could create a car if I had a good picture of the front, side and back of the car. Next I would locate the position of the wheels and axles and mark them on my pattern. I would draw a line 3/8 inch from the bottom line of the box to represent the axle height for the car. I would draw the position of the wheels and finish drawing the car around the wheels. If the car did not look proportioned correct on the pattern, I would erase the wheel location and try again. This was all done based on a visual observation of the picture of the car. Once the drawing looked satisfactory, then I would proceed to cut out the pattern and draw the image of the car on the block by tracing around the pattern. Once the design was transferred to the block, the block was ready to go to the wood shop to cut out the wheels wells, axle holes, and the shape of the car. Most of the time the cars looked good with the wheels in the right place and the cars shape proportioned correctly. No car measurements were ever needed because I was taking the shape of the car and fitting it into the regulation size block. There were still problems to be overcome due to warped blocks, bad measurements, and inaccurate patterns used to make the cars, but the system worked well for years with most of the projects I attempted.

I tried to make the form of the automotive sculptures as precise as possible. I began to make the patterns for the new group of cars using the same system I had used for the race cars, except I did not limit the size of the car. I had to continue to use the Pinewood Derby car wheels because I did not have another source. I had gathered pictures of the cars that I wanted to carve and began the process of drawing the patterns based visually from the pictures I had gathered from magazines and drew the patterns for all the cars as I had always done. I spent my night’s transferring the patterns to the blocks of wood so I could take them to the wood shop and cut out the cars. Jim’s wood shop had a 10-inch table saw that I used to cut out my blocks to make the cars. Some of the woods I used were what I call “on the hoof”, which refers to complete logs or limbs that I have found. I take the logs and reduce their size with a combination of passes through the table saw and an axe and hammer to separate the large pieces until I can get something the right size to be able to cut square with the saw. The 10-inch table saw limits the size block you can cut because I like my last pass with the saw to have the wood block a size where the blade will cut the entire side with one pass. As a result, most of the blocks are a maximum of three inches wide. Jim had a large band saw that was capable of cutting a board larger than three inches however I did not make any car blocks wider than three inches for this group.

I have known that the cars in the past have been narrow but that was required to meet the race car specifications but sculptures have no specifications and I did not think about how this would affect the car results. When Jim said I could use his table saw, I began to gather old logs I had in my garage to make blocks for cars. The oak I used on the Impala had been a log I had found in a trash pile on my way to work one morning. The oak had a soft pink-orange color and it reminded me of the color used on the original car. The sections of rot made yellow colored highlights in the wood giving the car a spectacular contrast to the pink-orange color with darker colored oak grain. Once I started carving the Impala, I learned the wood was hard despite the condition it looked. I was able to carve small details in it like the car like the “V” shaped hood insignia and the ‘eyebrows’ in the leading edge of the hood. The fins were harder to carve than I thought and any mistake in the edge of the fin would change the shape and look very obvious. I did not try to carve the outline for the doors into the car because I wanted to emphasize the long low look that the car was known for.

When I completed carving the Impala, I took the car to my friend Dave’s house where he was photographing some of my cars for me on a carousel he had made. I wanted the Impala to be included in the photography session and I worked hard to get the car completed on time. I showed the car to Dave and he liked it, but as he examined the car more closely he said, “There is something that is just not right about this car”. I realized the car was narrow and the thin body made the car look longer; but that was not the problem. I left wondering what Dave had seen. If you have a passion for an activity, a mistake will take you back to the drawing board with an unquenchable urge to correct it. Dave’s words haunted me and I took the car back with me and studied it. I measured the car several times and looked at my pattern to determine what Dave had seen. I researched the car and found the actual dimensions of the car and compared them to the proportions of my carved car. I learned that the overall length was correct, but the wheelbase was too long. I had always created patterns from a visual observation of a picture from a book or magazine because many of the cars I have carved, I have never seen.

The problems illustrated by the 1959 Chevrolet Impala were the same that I had been dealing with for years where a bad pattern caused problems with the final car. As I did my research I learned that pictures in magazines distort many of the images of the cars. I had looked at those images and I simply drew the distortion into the patterns. Looking at the actual dimensions next to the pictures of the cars made the problem too obvious. I had created the 1959 Impala using a free-hand drawing based on a picture to create the pattern for the car. I did not realize at the time that this car was one of the last cars made using that method since now the method had become obsolete. I could not afford to cut out and create cars from expensive exotic wood that had the potential to be defective from the start. I knew that I needed to change something. I liked the size of the cars I was making because they were small enough to be portable and a comfortable size that fit easily into my hand when carving. I knew the problems with visual based patterns and I had to correct it before moving forward with any further production. As a result, I stopped producing cars for over a year while I worked on a way to improve the car pattern making process. The 1959 Chevrolet Impala was a car that evolved through many different developmental stages to become the classic car that history has proved it to be. The humble beginnings in the early 1950’s paved the way for the low wide sedan with the outrageous fins by the end of “the era of the dream car”. I carved the 1959 Impala because I wanted to carve the cars with the largest different shaped fins that I could find and create a car series of these ‘finned’ cars for my collection. I did not think that making this car would set in motion a complete change in the process that I had perfected and used for so many years. The issues with the visually based pattern system were not a problem with the racing cars where the body was distorted to adhere to the strict Pinewood Derby racing specifications but had become too inaccurate to produce high quality automotive replicas that were to be judged solely by their appearance. I looked for a new direction to take the cars since the path I was on lead in a direction that I could not afford to go. I invented this journey and I must persevere knowing I will experience new problems requiring creative solutions in the quest to produce the historic automotive sculptures that I am determined to create.

The 1966 PONTIAC GTO Carved 2012

In 1963 the Pontiac Motor Division of General Motors was at the edge of a paradigm shift. The management of General Motors had issued a ban on any involvement in automotive racing and Pontiac had based its marketing plan on performance and racing, so its strategy had to change. Pontiac was know as “the old man’s” car division in the late 1950’s and was in the process of transforming its image at this time to attract the youth market and it needed competition for the soon to be released Ford Mustang. However, the General Motors management did not want Pontiac to have a high performance car in its product line because they feared alienating its older conservative customer base and the threat of the government breaking up General Motors because of its market dominance.