Without activity on this site for some time, I hope you don’t think we’ve abandoned you. It’s just that Rollo has been moving his many artistic pursuits faster than his nimble fingers can type. Don’t be discouraged, He’ll be back before you know it!

Category: Uncategorized

Slinging Scotia

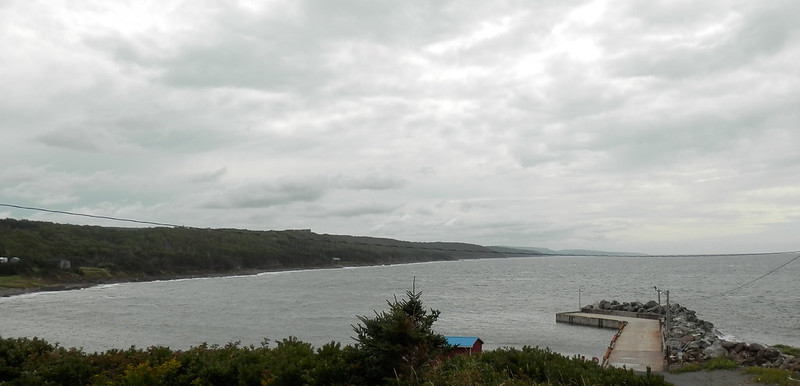

I traveled to Cape George, Nova Scotia this year for my vacation allowing me to escape the destruction of Hurricane Irma, which went over my Hoggtowne House. Knowing I was painting at the Cape, I bought paints on the way up in both the US and Canada.

I also bought tarps to paint on and tarps to set the finished paintings on to dry. I also built drying racks in the wood shed of the cottage I where I was staying so I had a place for the paintings to dry.

I knew that I only had a few days to paint because the paintings had to be dry before I returned home.

I traveled around the area and took pictures and returned to the cottage to paint. I created a “Studio in the Meadow” above the cottage overlooking St. George Bay.

As soon as I began painting, I realized that Canadian paints work differently from American paints. Canadian paints were harder to blend because they required more force and water pressure to produce the desired affects, so I ended up slinging most of the paintings to create the mixing affects I wanted.

When the paintings were dry, I moved them into the cottage and placed them on tarps to finish drying.

I created sixteen paintings in ten days. I gave away a couple as gifts and the rest of the paintings can be found at Red Horse Antiques and Gift Shop in Ballantyne’s Cove, Nova Scotia under the care of Mr. Charlie McDonald.

Here are the paintings and some of the places I painted. I hope you enjoy them as much as I did creating them.

1951 Bentley Continental Fastback

1951 Bentley Continental Fastback

The early 1950’s were a sobering time in Britain. The island was left devastated by the war and the commodities and luxuries that were once commonplace were still subject to rationing. Rising taxes combined with frozen wages kept the average person struggling. When gasoline rationing was lifted on May 26th 1950, people began to drive their cars again; however automobile manufacturers were dealing with limited resources and a clientele with less money to buy their products. With the economy improving, business began to improve after the end of gas rationing and The Director of Bentley’s Experimental Department was given a top secret project known as Corniche II to prepare. The goal was to create a fast luxurious two-door, four-seat grand touring vehicle. This special vehicle became the R-Type Continental.

Rolls Royce had bought Bentley Motors in 1931 and had simply rebadged their smallest cars as Bentley’s to keep the marquee alive. Roads were improving and other brands were creating better performing cars, so Rolls-Royce recognized that they would have to further develop their cars to keep them competitive and current. Rolls-Royce asked the Bentley engineers to create a car that could sustain high maximum speed for Continental touring on the long straight roads of Europe. The car had to have excellent acceleration and handling to compliment the high speeds, and the engineers were to find a solution using the Bentley 4 ½ litre car.

The Bentley engineers decided to test one of their 4 ½ Litre cars to the Bristol wind tunnel and they discovered that the car was more efficient running backwards. The engineers learned the exterior shape was inefficient and inhibiting the top speed of the car and a new shape was needed. The big problem was the large grille had the aerodynamics of a brick wall, but it was an intricate part of the brands image. Designers felt that changing the grille would alienate to Bentley’s conservative customer base, so the engineers were told to find a solution to the problem, but first they needed a buyer for the experimental car before starting work. They found an enthusiastic sponsor in Greek shipping magnate André Embiricos who desired the low drag 4 ½ litre coupe.

Bentley commissioned Georges Paulin, who was a dentist by trade and a French Resistance war hero but also a part time automobile designer, to design the new body of the car. Paulin had impressed the engineers with his work on Darl’mat Peugeots, and was considered one of the top French stylists at the time. It has been written that everything that Paulin designed had aerodynamics in mind. He was concerned with fuel efficiencies and aerodynamic efficiencies that could be created by the lines of the car. Paulin believed that aerodynamics allowed you not only to go faster, but be able to use a smaller engine in the car. Paulin penned the shape of the new coupe that was similar to the Talbot Lago, which he had designed earlier. The design included the cowled radiator cover and teardrop shaped fenders with covered wheels to further lower the car’s drag coefficient.

The Bentley engineers modified the 4 ½ Litre motor and produced a lower radiator to accommodate the new design before sending the chassis to Pourtout’s workshop in Paris, who was Paulin’s coach-builder of choice. Pourout’s craftsmen created the body mostly from aluminum to keep the weight down. Even the frames for the seats were constructed of aluminum saving over 100kg on the car. The finished product was a revolutionary streamline design combined with mechanical advancements and light weight coach work to create the world’s first true ‘super car’ forty years before the phrase was created.

The Embiricos Bentley was completed in the summer of 1938 and immediately sent to the Montlhéry track south of Paris for speed testing. The car was reported to have barely topped 100 mph, but it handled well. Embiricos took delivery of the car soon after the test, but he returned the car for further testing. Improvements were made and the car broke a speed record set by a Mercedes Benz. Engineers selected larger wheels and found the car’s speed improved, averaging over 110 mph on a four mile section. Embiricos sold the unique Bentley to HSF Hay in 1939. Hay put over 60,000 miles on the car, before he entered the car in the first post war edition of the 24 hours of Le Mans in 1949, where he came in 6th place. Hay raced the car two more times and placed 14th and 22 nd place in those races with over 120,000 on the car. Hay sold the Embiricos Bentley in 1969 having owned the car for thirty years.

The original reservations about streamline design were partially correct. The car demonstrated superior performance, but the Embircios Bentley was not well received because the styling was clearly too advanced for the average Bentley customer, and no more 4 ½ litre chassis were sent to France for similar treatment.

At the time Rolls Royce management was concerned and divided as to whether the market was ready for such an expensive and high powered vehicle. Once the signal to start development was given, the director of Bentley’s Experimental Department, Chief Project Engineer Ivan Everden began working on the top-secret project in 1950 known as Corniche II. Everden used the Embiricos Bentley as the design to start the development.

In order to achieve the lofty ambitions for the car, extensive research and testing was performed using quarter-scale models at the Hacknail wind tunnel. The extensive testing and alterations allowed Ivan Everden and John Blatchley of the Motor Car Division, to design an aerodynamic body that reduced drag and had excellent stability at speeds in excess of 100 mph. By late summer of 1951, the drawings and scale models had become the prototype R-Type Continental named OLGA after the register index number “OLG 490”. Every effort was made to produce the car with the lightest material available including aluminum bumpers, body panels, window frames and seat backs. Non standard tires were used and radios were only added at customer’s request. The results were that the car was able to reach a quarter mile in 19.5 seconds which was an amazing achievement at this time.

Bentley displayed their new R-Type in 1952 at the Earls Court Motor Show. Bentley said the R-Type was available in a two-door Continental or Saloon. The look of the R-Type Continental was one of the most striking things about it. With raised front wings that swept across the doors, before tucking into the rear of the vehicle, curved windscreen, smooth fastback, and fin-like rear wings all-together made a breathtaking car. The R-Type Continental was the closest Bentley came to adapting Paulin’s aerodynamic ideas, but the Continental and most of its successors continue to retain the large upright “Bentley radiator”, however the Bentley Continental R is still considered one of the most beautiful cars in British automotive history.

Testing of the new Bentley began in September of 1951 in France under the direction of Walter Sleator, who was an ex race car driver and the Rolls Royce agent in Paris. After extensive testing and refinements, production began in early 1952. The Bentley Continental R became the fastest production four-seat car in the world capable of speeds over 100 mph and performance that eclipsed many sports cars of the era. The combination of light weight construction and the sleeker body style resulted in performance that was superior to any Bentley produced after the war. The chassis were assembled in the Crewe factory and sent by rail to the coach builder H.J. Mulliner in Chiswick. All of the Continentals ever produced for Bentley would be coach-built, and therefore, very distinctive. The Fastback featured a steeply descending rear end completed by a boot handle and the Bentley logo. All but 15 of the 208 Bentley Continental’s were fitted with the fastback bodies. The cars were produced between 1952 and 1955 with the A, B, and C, models were fitted with 4.5 litre motors and the D type was fitted with a 4.8 litre motor.

The Bentley Continental R was designed to be driven by the owner-enthusiast and was considered the vehicle for the sportsman who wanted to drive far and fast. Nothing was held back on this car with the top speed of the car was said to be 118 mph, but the controls and steering were heavy, and the fuel consumption was described as ‘fierce’. Testing showed that when the car was driven hard, that it consumed tires at a ‘phenomenal rate’ and it was not stable in wet conditions. The interior was filled with leather, carpet, and wood of the finest quality, but performance was the most important feature of the car. In 1952 the Continental R sold for £7,608 and all of the cars were built for export. The price was part of the appeal and the car was the considered the ultimate automotive status symbol at the time. The Bentley Continental R was an extremely well built car and most have outlived their first owners, and the majority of them are still raced competitively in rallies today.

The Bentley Continental is one of my favorite cars of all time. I have loved the use of parallel lines in the body at various places to create the image of a speed. For example, the shape of the front fenders and the hood make a series of gently rounded parallel arcs that are accentuated by the highlight on the side of the fenders that runs down the side of the car leading your eye to the long fin shaped fenders in the rear coming to a point with the intersection of the sloping body that tapers down to the bumper. The peaks on the top of the fenders run parallel to the smaller peaks of the headlight cowls. These parallel lines combined with the sloping shape of the fastback design produce the flowing feeling the car’s image projects. These details caught my eye when I first saw the car in a book over 20 years ago and they are just as powerful today. I tried to carve the Continental when I first began carving cars, but I had not figured out how to put wheels on the cars at that time and the car sits unfinished, but it will be features in the Studs at a later date.

I carved the Bentley Continental as the second car in this series after I had carved the 1930 Nutting-Bodied Speed-Six known as ‘The Blue Train Bentley’. The experience of working with the mahogany wood was helpful in making this car. I thought that the even grained wood would enhance the details of the body of the car and my ideas proved correct. The even tone of the wood with no grain highlights emphasizes the details I carved in the car. I knew that the wood was hard to work with my pocket knife, but the section of the board I used for this car had less cross grain sections than the Bentley Speed Six. The only problems I found were small sections on the fenders, and I had to make sure that the tearing of the grain did not create low spots on the car’s surface. I kept the knife very sharp when working with this project and I was careful to take my time and get the details correct. I highlighted the trim line around the fender and slowly carved back the fender section, allowing the highlight to emerge from the original cut block, but if the wood grain had come out in a section and tore from the car, this detail would have been lost.

I have a motto when cutting out the car shapes from the block that I ruin the cars with the saw and fix them with the pocket knife. I was lucky that I had left this car cut large, meaning that the saw cut outside the marked lines of the pattern and gave me the material to mold the rounded surfaces of the body panels like the hood and roof lines. I had foolishly attempted to cut the fender intersection at the rear slope area with the saw and it left a deep mark on the back of the body of the car that I had to cut out. I have dealt with these deep cuts many times and the saw will gouge the wood and as you cut out the line. The remaining part of the area must be cut down to maintain the shape of the body you are trying to create, so these ‘gouges’ can add distortion to the shape. Luckily I was able to cut out the gouge in the rear of the Continental and maintain the sloping body shape.

Cutting out the rear fenders was another challenging task since the fenders had to be the same width and the area where the fender formed and separated from the body had to be made. The back side of the fender needed to be created to make the slope running down the body to form the fast back. I felt this area was critical to the success of the design, and had to be executed properly. This area was the same area affected by the gouge from the creation of the fenders from the fastback and took special attention to maintain the form. I took a long time working on this piece as I carefully worked out these details and rounded the surfaces of the body to recreate the car as close to the original car as I could create. I took special care carving the front area of the car and creating the inset headlights and the rounded grille. I made the hood ornament with the knife and I had the same problems as the ornament on the Speed Six. The Continental’s hood ornament broke in half as I was started carving it causing panic. I worked with the stump that was left, and I was pleased with the small wing structure that I carved and thought that this design came out better than the Speed Six hood ornament.

I decided to finish the car with the knife marks left in the surface, but since the wood was hard, these marks were very small creating a smooth texture on the surface similar to a sanded surface and they helped highlight the form. I did not want to sand the car because I was afraid that would eliminate the fine details I had worked so hard to carve. The subtle details came alive with the contrast of the smoother wood of the body panels. I finished the car with a hand rubbed bees wax shine to bring out the grain and produce a shine to the wood. The soft brown tones of the wood with few grain highlights emphasized the fine details of the car when in proper lighting.

The Bentley Continental was a benchmark for Bentley created in one of its darkest hours. The car was produced at a time when few resources were available and the management at Rolls Royce had demanded tight time tolerances for the development of the car, but the Bentley engineers not only managed to produce the car within the tight parameters, they produced one of histories truly great automotive classics in the process. I was most excited about carving this car again because of my love of the challenging design and I wanted another attempt to produce this car. My abilities have improved since my last endeavor and I knew that the combination of rich colored wood and the better execution would make this classic car one of the most spectacular of my collection.

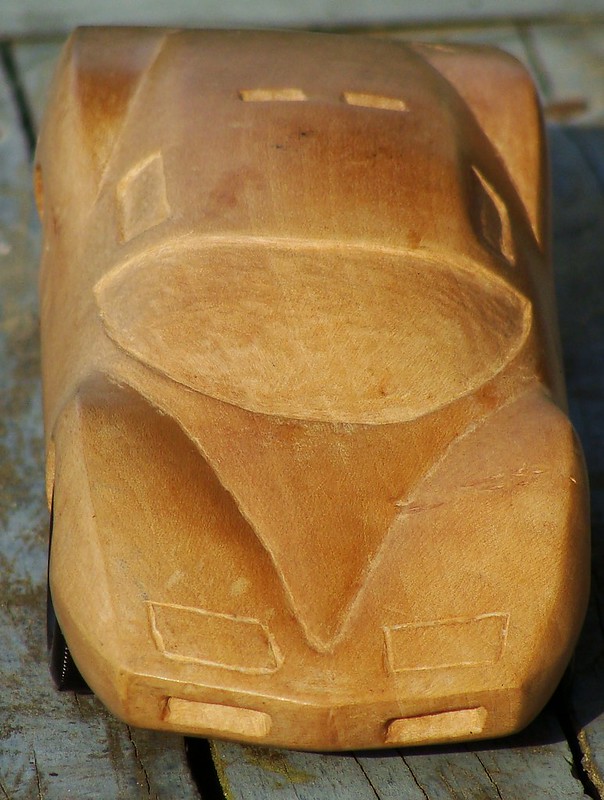

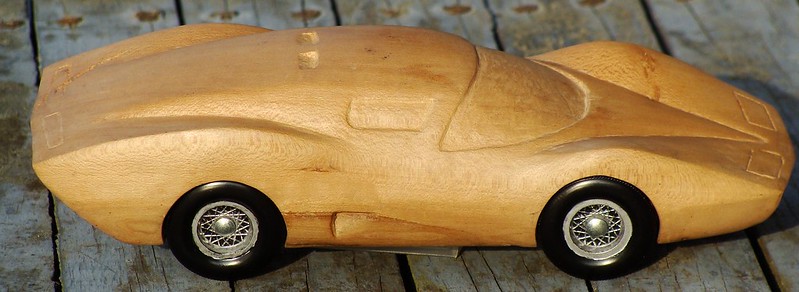

1992 Vector W8- Carved in 1993

Jerry Weigert had a dream while he was in college to create America’s first super sports car. After graduating from college, he formed a company named Vehicle Design Force based in Wilmington California and built a shell for the car with the help of Lee Brown. They named the car The Vector and planned to power the car with a Mercedes-Benz Wankle-design engine. The motor was never built and Lee left the company leaving the prototype unfinished. In 1972 the company name changed to Vector Aeromotive Corporation and a new “shell” was created named the Vector W-2. Various power trains were adapted to the car in the 1980’s, however in 1991 the W-2 was redesigned with the help of David Kostka, and it was renamed the Vector W8. The Vector W8 had a V8 motor producing 600 hp and an estimated top speed over 200 mph. There were only 19 cars ever produced and 2 of those were prototypes. Vector cars were expensive and high production costs mixed with poor quality construction caused the company to go bankrupt in 1993. An Indonesian company named Megatech bought the company and moved it from California to Florida. Weigert split from the company but he had copyrighted the designs for the W8 and the WX-3 before he left.

The Vector W-8 featured an aluminum honeycomb floor with a semi-aluminum monocoque chassis with the body composed of light weight carbon fiber and Kevlar. The engine was a Rodeck modified Chevrolet 350 Cubic Inch V8 with twin turbo chargers that produced 650 hp. The transmission was a 2-speed automatic that can be shifted manually. The interior included a modern cockpit with leather seats and a CD player, and a large electroluminescent display monitoring all the vital engine information which created an aircraft-like cockpit with interchangeable displays. The Vector was tested at the Bonneville Salt Flats and the car was able to achieve 0-60 mph in 4.2 seconds with a top speed of 242 mph. Road and Track tested the car in March of 1991 and August 1992 and found the Vector W-8 outperformed Lamborghini, Ferrari and other exotics supercars which lead the magazine to declare that the Vector W8 was the fastest production car in the world. The McLaren F1 was the only supercar to outperform the Vector W8. The car originally sold for $448,000 new, however on today’s used market, they are available from $389,000 to well over $1.4 million depending on the condition of the car.

I first heard of the Vector in 1992 when I bought a copy of Road and Track which featured the car. I was making Pinewood Derby race cars at the time and I based my pattern designs on visual observations based on pictures from magazines. I made the cars to meet Pinewood Derby specifications so the cars could race on the Pinewood Derby track. I was trying to create hardwood cars to run in the Pinewood Derby City race in McIntosh Florida and I wanted to copy the fastest cars in the world for my collection; so when I read about the Vector I knew I had to build it.

The wood I chose to build the car is Beech wood from North Carolina. My work supervisor was taking a vacation to North Carolina and asked I asked for a log if they had time to find one. Phil brought me back a limb that I had to square with a saw to be able to use it. Once the board was made, I learned the piece had seven knots in the wood, which made it terribly hard to carve because of the crotch grain pattern in the wood. The wood had a pink color and a minty scent when I carved it. I worked on the Vector for a long time fighting the grain of the wood, which was tough and had a tendency to split. The Vector had one of the first spoilers that I carved that was open on the bottom. The Beech wood is tough, but is not brittle which made it good for carving challenging details like the small spoiler. I tried to carve all the various vents on the car and as much detail as I could to make it look like the actual car. Although the pink wood was hard to carve because the grain structure, it held a tight edge and I could make precise details. The wood is dense and the hand-rubbed bees wax finish produced a nice smooth satin finish.

The Vector was created during the time when I was concentrating on making fast Pinewood Derby race cars that ran on the Pinewood Derby Track. I had raced a Cherry F40 and a Cherry Ferrari Testarossa the year before and experienced great success winning the McIntosh City Race with the F40 coming in first place and the Testarossa a close second. The Vector’s design has its front end stick out in front of the car with a low spoiler under the front end by the front wheels so the nose suspend above the track. I felt this would give the car an advantage in the race since it would have a quicker start off the starting block and the nose would stick out at the finish line giving the car an advantage if the race was tight. However, none of that matters if the competition is fast enough so there are no tight races.

The Vector raced on a night where the competition was strong. The night of the McIntosh City Race was exciting and I had carved a fast group of cars for the race. They included the Lamborghini Countach made from Black Walnut; the Lamborghini Diablo made from Magnolia; the Jaguar XJ220 made from Holly; the Porsche 959 made from Bay; the BMW M3 made from Silkwood; and the Corvette Grand Sport made from Mulberry wood that I found on the edge of Payne’s Prairie when I was driving to work early one morning. The Diablo and the Vector were very fast cars and won most of their races; however the Jaguar XJ 220 was the fastest car that night. The Vector was one of the most unique designs of the cars that I carved that year and one of the most challenging cars I have ever carved because of the crotch-grained wood. I try not to carve wood with crotch-grain after the knowledge gained from carving the car.

The 1967 Astro I – Carved 1994

The Chevrolet Corvette has had numerous concept prototypes made to explore the design alternatives for the vehicle. Most of these concepts never made production but they give a glimpse of the future direction of the design. The Astro I was one of these designs. The car was designed under the direction of Bill Mitchell but the actual work was led by Larry Shinoda. The design originated from a sketch drawn by Bill Bowman while he was in Hank Hagga’s Chevy 2 Studio. Mitchell selected the sketch and instructed the design to be developed into a running car. Bill Bowman was sent to Larry Shinoda’s off-site studio called The Warehouse to develop the car with several modelers and an engineer. Mitchell was the driving force behind the development of the car and it was Larry’s job was to make sure that Bill developed the car on Mitchell’s schedule. The design team felt the car was developed off-site so the car could be raced at 24 hours of LeMans race because of the high-output Corvair motor in the car. General Motors had banned all corporate sponsored racing at this time and used the “off-site” studios to develop their racing products away from scrutiny.

The purpose of the Astro I concept was to design a car with the lowest drag coefficient possible. This was achieved by a low roof line, a small frontal area and a relatively high rear end. Engineers wanted to study aerodynamics knowing that the frontal area and shape were major factors to determine the drag coefficient in high-speed air, but this was a new area of study when this car was created. The running prototype was built but the aerodynamic properties of the car were never proven. The Astro I resembled the Mako Shark show car and predicted the shape of the 1968 Corvette with twill rectangular grills and hide away headlights on the leading edge of the hood. The rear featured pop-up panels for air braking and air extractors on the rear deck that vented the engine compartment heat. The small tail lamps were located in simulated vents on the rear of the car. The overall height of the car was a low 35.5 inches, so conventional doors would not work. A clamshell entry system was designed where the entire body behind the windshield was one piece that lifted up and backwards with a large screw mechanism. The two bucket seats would rise to help occupants get into the car. Once the driver and the passenger were inside and strapped in, the clamshell lowered down and the seats lowered back into position so the driver could use the aircraft inspired control panel and the twin stick steering wheel to operate the car.

The low profile of the car eliminated the use of a conventional V8 engine so a special horizontally opposed six-cylinder Corvair air-cooled motor was developed, but this was never promoted. The Corvair flat-six engine was used because of its height and it was fitted with a special cooling system using three centrifugal blowers which also kept the height low. The motor featured a single overhead cam valve train, hemispherical heads and inclined valves with a pair of three barrel inline carburetors. The castings design placed the carburetor barrels right over the ports for the fuel mixture to have a straight shot at the valves. The Astro I also featured independent suspension, four wheel disc brakes and special custom control arms at each corner of the car.

The Astro went from a final sketch to a running prototype in five weeks and the Astro I was one of the rare instances where a designer’s vision became a running car with no changes. After the racing program was canceled, the Astro I became a show car. Although the Astro I never ran, it was a huge hit for both Chevrolet and the GM Styling team. The Astro I was never intended for a production car but it included a variety of innovations that made their way into production. The Astro I Concept debuted at the New York Auto Show in 1967 and was shown around the country afterwards. I remember when I was growing up that new cars were introduced in September of each year with a big advertising campaign and new cars would always be on display at the Mall so shoppers could see the new offerings. I remember on year that Chevrolet had a special show that featured the Astro I with the latest cars for the next model year, and my father took me to see it at the local Mall. This was the first concept cars I had seen and it left a lasting impression on me. I remember the color of the car was pink, although most of the photos I have found of the Astro I are red and black. The car was shown with the clamshell opened so you could look inside and I remember dreaming about what it would be like to drive such a car because it was the most fantastic car I had ever seen. The car was the highlight in a show that traveled to various cities. I remembered the car for years, but never heard of the Astro I again after that car show left town, but I did not forget that pink silhouette that left such a lasting impression on me.

I had made several Pinewood Derby race cars before 1994 and I felt that I understood the process and I began to branch out and look for innovative designs to use for my race cars. I searched various magazines and books for designs to carve because I had limited access to the internet at the time. I remember that I came across a picture of the Astro I in a book on experimental Corvette’s and I remembered the car and was determined to make one. I remembered the car of my childhood was pink and I wanted to make one the same color. I had made a bright pink Cadillac from a piece of Dogwood and I found a cut limb in a trash pile and took it home to make the car.

Dogwood is very hard to carve and it has a tendency to split and check because the wood held water. The piece I carved the car from was a block I had cut from the limb that split down the middle. The Astro I was so short, that I was able to make the car from the section that was left intact. The wood was very hard to carve and took a long time to make, but I was able to carve the fine details since the dense hard wood made a tight precise edges.

The Astro I was created as a Pinewood Derby race car and the dimensions for the car a based on those racing specifications. The pattern for the design was made from visual observations from pictures and no specification information was used. The wood was hard to carve and I remember struggling to get the details carved on the rear of the car. This was during a period where I began to add more details to my work. I sanded the car smooth with #600 grit sand paper and hand-buffed the bees wax finish for a lustrous shine. The bright pink wood had no exotic grain and has a nice even color that emphasized the details in the body.

The car looked great and it performed admirably. Dogwood is a very dense wood so the car was very heavy and ran very fast on the track. The Astro I was the fastest car in the preliminary races, but the 1967 Mustang made from Oak beat it after a wheel repair. The Astro I was the second fastest car at the McIntosh City Races in 1994 but one of the best looking of the cars I carved that year.